Monarch Monitoring with the YOCO Program at Prince Edward Point National Wildlife Area

Categories: Education; Research; Advocacy

Written by Ketha Gillespie

The second year of PEPtBO’s Young Ornithology Career Orientation (YOCO) program is coming to an end. The youth are, of course, learning about birds, but they are also gaining knowledge about the various habitats of the south shore and all of the living creatures these habitats support. We were very excited to have the opportunity to work with a Canadian Wildlife Services (CWS) intern to learn about monitoring the population of monarch butterflies within Prince Edward Point National Wildlife Area..

First things first - finding monarch eggs is not easy. Our search started in a big patch of milkweed where we looked for eggs on the underside of the leaves on the milkweed plants. The eggs are as small as a pin and oval shaped with lines or ridges on the outside. Since the eggs are not easy to find, we were also looking for the monarch caterpillar in different stages of development, known as instar and categorized using a scale of 1 to 5 (Fig below). Caterpillars range in size from 2mm to 45mm.

Instar Phases

The monarch caterpillar in different stages of development, known as instar and categorized using a scale of 1 to 5.

During the summer months the monarch butterfly will lay up to 300 eggs and only a small percentage of these will hatch, grow, and finally form a chrysalid, to become a butterfly. These summer butterflies have a short lifespan of 3 to 6 weeks and their job is to lay eggs. It does take a few generations of monarchs to reach us here at Prince Edward Point Bird Observatory, because the butterflies are laying eggs all the way up the ‘monarch highway’ from Mexico.

One of the YOCO participants asked a great question: ‘Why are monarchs so important, are they really that great a pollinator?’ In fact, they are not the best pollinators out there but they are widely recognized as one. We consider monarchs the “poster” pollinators of North America. They are seen in both urban and rural areas and many people can readily identify them. In Mexico - where they arrive en masse - it is believed that the monarchs are spirits of the ancestors, as their arrival coincides with the holiday Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead).

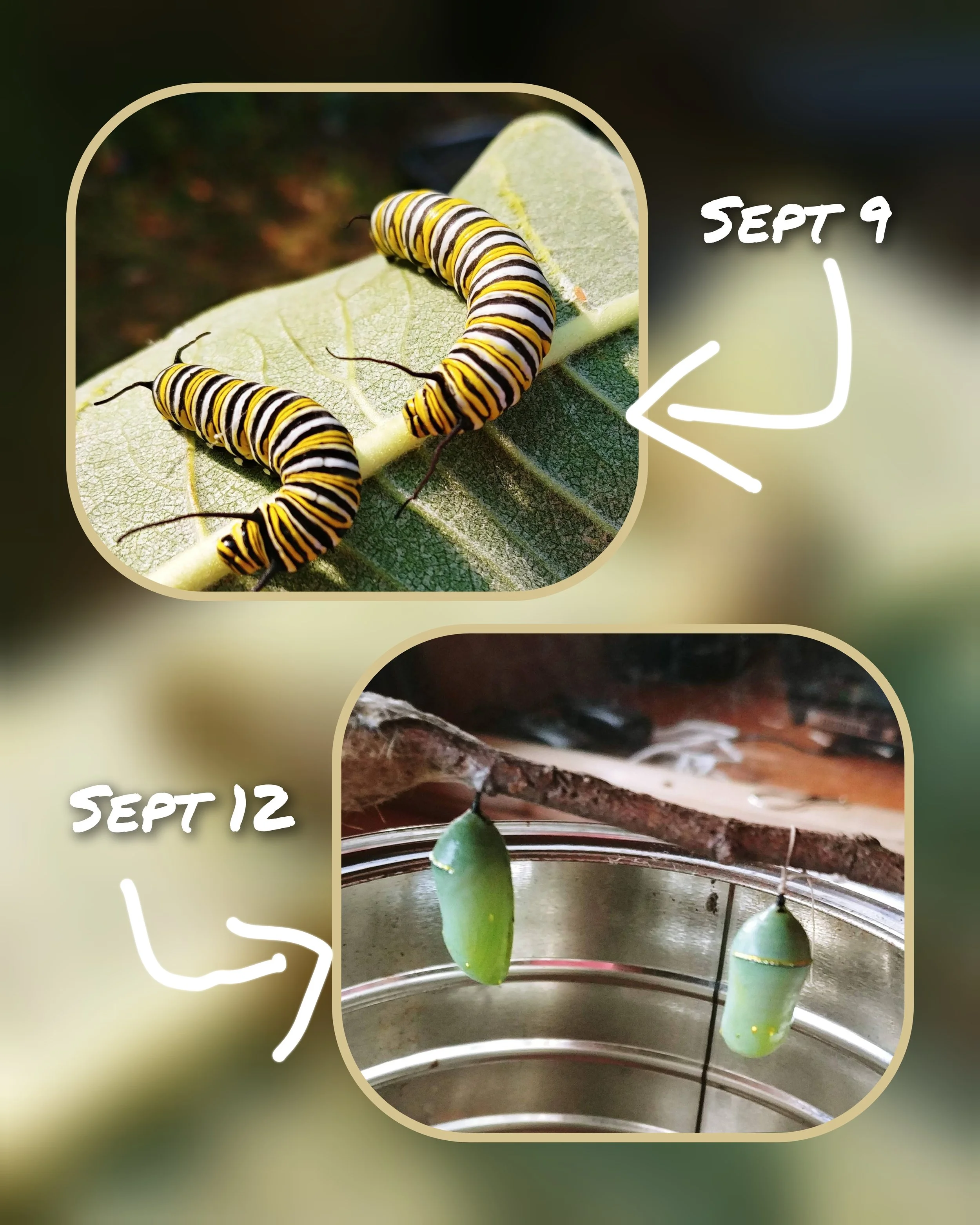

As we found the different sizes of caterpillars we were able to identify the instar stages and locate the caterpillars that would be forming chrysalids soon (Fig 2). The butterflies that emerge at this time of the year are the ones that will make the long trip to Mexico. These butterflies will have a much longer lifespan of 7 to 9 months, and during this time will lay no eggs and spend all their energy flying to Mexico to overwinter in the mountains.

Caterpillar to Chrysalid

One of the things that we as ‘monarch warriors’ can do is raise them indoors as a teaching tool. By looking for and rearing these caterpillars inside you can save them from getting mowed and witness the wonder of nature. Each caterpillar will need 1 fresh milkweed leaf to live and grow as well as a couple of sticks to help with the formation of chrysalids. Most monarchs will be fine in their natural habitat and, of course, we don't take anything from the National Wildlife Area but areas that will be mowed are fair game. The process of chrysalid formation can happen very quickly and once the chrysalid has formed you can observe the transformation from chrysalid to butterfly.

Changes in Chrysalid

I plan to take the caterpillars to a local kindergarten class so that kinders can engage in nature in their classroom. I believe that a big part of nature education and conservation begins with people building a relationship with the natural world. For some kids, witnessing the monarch life cycle (below) can be the start of a life long connection to nature.

Monarch Life Cycle

You may be wondering about the current status of the monarch butterfly population and how you can get involved in conserving this beautiful pollinator species. Unfortunately, the most recent research indicates a decline of 96% in 2024 - a drop the size of which we haven’t seen since 2017. Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation has been monitoring monarchs on the California coast and in the Baja mountains for the past 28 years and recently found the numbers for 2024 the second lowest since they started monitoring. The highest counts saw 1.2 million in 1997 down to 230 000 during the winter of 2023 and to a low number of 9,119 (from winter 2024).

There are many reasons for the decline in the number of monarchs: climate change, predation, loss of habitat, disease and pesticides. Let’s all do what we can to support the monarch population - add milkweed to our gardens, stop using pesticides, plant native flowers and replace our lawn with flowers or vegetable gardens. By doing these things, we will also be helping other pollinators such as bugs, bees, and birds. When we work together to build relationships with our natural world, all living things benefit.